by Jeff Fleischer

(Mental_Floss, November/December 2007)Hieroymus Bosch managed the rare feat of becoming a famous painter in his own time despite spending virtually his whole life in the village where he was born. By confining his travels to his own vivid imagination, the deeply religious Bosch created incredibly detailed visions of sin, judgment and punishment that still give viewers the creeps today.

Bosch was born Jheronimus van Aken sometime around 1450 in s’Hertogenbosch, a town in the Duchy of Brabant (today part of the Netherlands). Not much is known about his early years, but he had the good fortune to grow up in a family full of painters; his father, grandfather, brother and three uncles shared the same job. Bosch learned his craft from some combination of them, and built his first workshop in his twenties with guilders on loan from dad.

Still, he literally made a name for himself, Latinizing his given first name and dropping his surname in favor of an ode to his hometown. By about 1480, he had married a nice Catholic girl, the wealthy Aleit van den Meervenne. Far from a starving artist, Bosch was a prominent city burgher, and his reputation was widespread enough that royalty in several European countries bought his paintings.

A MATTER OF FAITH

By 1486, s’Hertogenbosch records show Bosch listed as a “ notable member” of the Brotherhood of Our Lady, a conservative religious organization dedicated to worship of the Virgin Mary. A lay member (once again, like his family), he handled a number of commissions for the well funded brotherhood, from stained-glass windows for its local church to since-disappeared cathedral altarpieces.

Some twentieth-century revisionists have accused Bosch of secretly belonging to any number of the heretical Christian sects that covertly operated in the Low Countries during his life. The most famous example was art historian Wilhelm Fraenger, who tried to link him to the sexually overactive Adamites (who believed, among other things, that orgies brought man closer to his original state).

But there’ s no documentary evidence to support these theories, and Bosch’s work – almost all of it religious in nature – consistently showed a terrifying, demon-packed hell awaiting all variety of sinners and fools. An outlook very consistent with his strict religious affiliation. Also, Bosch painted at a time when books were hard to come by (moveable type was first invented shortly before his birth) and art was still the best way to communicate biblical teachings to people. And, as Bosch showed, to scare the bejesus out of them.

DEADLY SINS

Bosch didn’ t make it easy for historians to catalog his work, never dating any of his paintings, but changes in his style do provide a rough chronology. In his early period, he painted a few works that weren’t religion-specific, but even those mocked the flaws of his fellow man. In “The Conjuror” (c. 1475), he paints a gullible villager mesmerized by a magician’ s trick while an accomplice picks his pocket. “ The Cure of Folly” (c. 1480) concerns a surgeon in a funnel hat using a scalpel to remove a stone from the head of an elderly patient (a superstitious procedure reputed to cure, of all things, stupidity).

Other early Bosch masterpieces included: “ The Seven Deadly Sins,” with an allegory from everyday peasant life for each sin; “ Death of a Miser,” in which a man on his deathbed collects a last bag of gold even as a shrouded reaper enters his room; and “ The Ship of Fools,” with a boat full of drunken singers (including a nun and monk) sharing space with omens of stupidity and hubris.

Those works paved the way for the seminal works of Bosch’ s career, a trio of oil-on-panel triptychs (three hinged panels that fold together) created in the early 1500s. All three featured a chaotic middle panel flanked by scenes of Eden on the left and of eternal damnation on the right.

“The Last Judgment,” the largest painting Bosch ever made, also packs the most raw dread into the frame. Here, the Eden scene is actually four scenes in one, from the fall of the rebel angels to the creation of Eve. The middle panel is the judgment itself, with Jesus rapturing a tiny minority of souls to heaven while the rest are subjected to all kinds of inventive torture – cooked in pans by demons, forced to dance nude for other grotesque monsters or impaled by various pointy objects. The demons themselves might be Bosch’s greatest contribution to art and pop culture, ranging from human-animal hybrids to fat witches with brightly colored faces to legged serpents with built-in trumpets and armor. “The Haywain” has a similar setup, with its middle panel built around a giant hay cart pulled by monsters as people fight each other on their way to grab some hay. Of course, their greed for a worthless worldly good is punished in the right hand panel, with more torture at the hands of demons.

PARADISE LOST

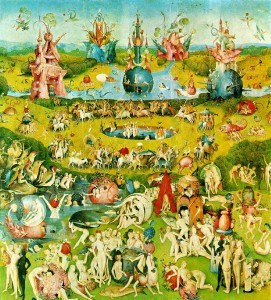

Bosch topped both those works with “The Garden of Earthly Delights,” with its fully realized vision of wild lust. The “ Garden” could refer to the left-hand panel, where God in the form of Jesus presents Eve to Adam for the first time and all kinds of animals populate the landscape. Or it could mean the center panel, where hundreds of naked humans overindulge in all of the world’s pleasures. Animals and plants grow to massive sizes, to the point that couples copulate inside giant berries. People enjoy sex, dancing, eating, drinking, cavorting with animals; pretty much everything they weren’t supposed to do in the 1500s.

Not surprisingly, Bosch’ s most over-the-top depiction of the fall from grace comes complete with his most graphic damnation yet. The hell of this painting features extra layers of irony, with musicians tortured on a giant harp and lute, a huge hollowed-out man used as a factory by demons, and the bizarre structures from the garden replaced with exploding buildings encased by darkness. Anyone intrigued by the rest of the painting couldn’ t miss the message of where Bosch felt such antics would lead.

Bosch’s later works included somewhat mainstream scenes from the life of Jesus, trading the hideous monsters of the triptychs for hideous expressions on the faces of deceitful men. And his surprisingly uneventful personal life continued its fairly mundane pace. Bosch probably never left s’Hertogenbosch before dying, and being buried by the local Brotherhood, in August of 1516.

Famous during his lifetime, Bosch became less so in the years after his death when the Italian Renaissance dominated the art world (Leonardo da Vinci and Bosch were born and died within a few years of each other). As Michelangelo, Raphael and others became popular, Bosch’s distinctly medieval style looked outdated. But his legend got a second wind 400 years later. Salvador Dali credited Bosch as a precursor to the surrealist movement, and paid homage to the “Garden of Earthly Delights” in his own “The Vision of Hell.” The budding psychoanalysis movement was also fascinated by the monsters conjured by Bosch’ s imagination; Carl Jung actually called him “the discoverer of the unconscious.”

—————

SIDEBAR: “The Garden of Earthly Delights” (Prado Museum, Madrid, 1490-1510)

Few painters packed more detail into their work than Hieronymus Bosch. Look closely for the following examples:

Wild Wildlife: In the first panel, the giraffe, elephant and dog are joined by more unusual creatures. A unicorn is among the animals drinking from the pool on the left side, while a three-headed lizard is one of those heading to land from the central water. Bosch even hints at a dark side to paradise, with a lion eating a deer near the top of the frame.

Looking Back: There’ s a cave in the lower right corner of the main panel. There, Adam and Eve – now covered in animal skins after their removal from Eden – observe the goings on.

Medieval Peep Show: Bosch doesn’t explicitly show sex. Instead, he hints at it throughout the main panel, with couples paired inside a glass bubble, a clam shell and pieces of rotting fruit. In the panel’ s center, nude men joyously ride a variety of animals – from horses and camels to griffins and boars – around a pool chock-full of bathing nude women.

Deadly Sins: Near the bottom of the hell panel (below the bird-faced monster eating and excreting sinners), people are punished for various sins. A glutton is forced to vomit into the same hole where a miser is depositing gold coins from his posterior. A vain woman sits nearby, staring at her reflection in the shiny rear end of a demon.

Some of the more subtle symbols in “ The Garden of Earthly Delights” were old standbys for Bosch, who used them constantly in his work.

The Owl: In the left of the center panel, a man hugs a giant owl. While the owl has long been a symbol of knowledge, in Bosch’ s hyper-religious era, “ knowledge” was frowned upon as a reminder of the fall from grace. In many of his works – including “ The Ship of Fools” and “ The Haywain” – Bosch used the bird’ s presence as a way to mock his characters’ folly.

Knife Inscriptions: One mystery is why, anytime Bosch painted a giant knife in one of his hell scenes (as he does here with the knife between the giant ears), the blade has a letter “ M” inscribed on it. Some theories? It could be shorthand for either the world (mundus) or male sexuality, or maybe just the initial of a particular knifemaker lost to history.

Fish: Like the fresh fruits that populate the center scene, the giant fish on the ground are symbols of ripeness and, therefore, of human lust. Many of the monsters in Bosch’ s visions of hell have the heads and/or bodies of these “ wicked” seafarers.

Tags: art, bosch, el bosco, el jardin delicioso, garden of earthly delights, hieronymous bosch, jeff fleischer, mental floss, painting