by Jeff Fleischer

(World Jewish Digest, October 2006)

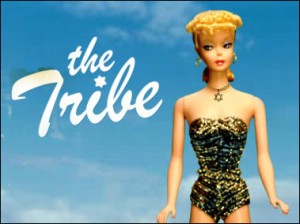

Since her creation in 1959, the Barbie doll has become one of the world’s most popular toys, with more than a billion sold around the world. While she’s adopted an assortment of occupations, physical traits and cultures in the past half-decade, Barbie started out with just one version—that of a blond-haired fashion plate living the mainstream American dream. She also started as the brainchild of Ruth Handler, the daughter of Jewish immigrants from Poland. For filmmaker Tiffany Shlain, Barbie was the perfect starting point for The Tribe, a short film exploring what it means to be Jewish in the 21st century.

“I knew I always wanted to do a film about Jewish identity,” Shlain told World Jewish Digest. “I had known the creator of Barbie was Jewish, which I thought was one of the great ironies of pop culture. So I thought it would be a very interesting way into complicated issues of assimilation and identity, which I’ve wrestled with myself.”

Shlain, 36, grew up in Mill Valley, just north of San Francisco, with what she calls a “culturally Jewish” upbringing. She attended High Holiday services at her family’s Reform temple, went to Sunday school and had a bat mitzvah. But growing up in a diverse area without a tight-knit Jewish community, she says she didn’t really feel engaged with her religion. As an adult, she didn’t belong to a temple or to Jewish organizations. She explored her heritage—visiting her grandparents’ former home of Odessa in the Ukraine, stopping at Auschwitz on a trip to Poland, honeymooning in Israel—but says she still wrestled with reconciling her Jewish roots and her assimilated life in America.

Then, in 2002, Shlain— also the co-founder of the popular Webby Awards honoring the world’s best Web sites—was invited to the first of the now-annual weekend retreats hosted by Reboot (a nonprofit organization that brings young, creative Jews together to network and dialogue about Judaism today). Already interested in issues surrounding Jewish identity, Shlain says she was impressed with how freely the 40 participants shared their personal stories and varying levels of comfort with their roots. She wanted to make a film that would spark similar conversations, without pushing an agenda.

As it happened, Ruth Handler died the weekend of the retreat. Shlain was struck that the obituaries failed to mention that Handler, the creator of the ultimate Shiksa doll, was Jewish. Considering it a perfect example of Jewish assimilation, Shlain realized she had found her film’s hook.

Along with husband Ken Goldberg, an artist and professor of robotics at the University of California-Berkeley, Shlain started writing. The result is an 18- minute film that uses Barbie to introduce larger themes of what it means to be a Gen X or Gen Y Jew.

The film has a Heeb Magazine, hip- Jewish vibe, linking funny images and ironic humor with more serious statistics and facts about Jewish history. The visual style is fast-paced and eclectic. Themes of intermarriage and interfaith, new attitudes toward Israel and Jews vis-à-vis African-Americans, all are touched upon as falling within the range of experiences from which today’s youth “roll their own” meanings of Jewishness.

Actor Peter Coyote (E.T., Jagged Edge) narrates the tongue-in-cheek script, which starts out by asking viewers to imagine the population of the earth as a tribe of 100 people. Shlain then breaks down that sample into sub-tribes, explaining it would consist of, among others, 30 Christians, 18 Muslims and one Jew, who is not even a whole person but a quarter of one, represented by a tiny red dot. From there, she points out that one member of that tribe created Barbie and adds, cutely, “All sub-tribes can agree Barbie doesn’t look Jewish.”

“Barbie is my shill in a way,” Shlain says. “She’s my way in. A lot of people see this film who would never see a film about Jewish identity, but they’ll see a film about Barbie. She’s a very fun pop-culture object to deconstruct. But of course, it’s a 15-minute film. Our goal is for the film to be the appetizer and the main course to be the discussion afterward.”

Shlain has held screenings all over the country—including the United Nations Association Film Festival—with audience participation sessions immediately afterwards. She says typical conversation topics range from what it means to “look” or “act” Jewish to new attitudes toward Israel to the differences among Jewish denominations.

To that end, the film introduces topics but does not dictate answers. At times, the narrative is fun and ironic, as when it includes a diorama of Barbie and Ken dolls in a bat mitzvah scene or when Jewish denominations from atheist to ultra-Orthodox are illustrated using Kens in tradition-specific getups.

But some of the visuals are serious, as when Shlain mixes in archival footage of buildings laced with antisemitic graffiti. Toward the end of the film, The Tribe even includes quick cuts of real “Jews on the street” describing their own self-definition. An attractive, stylish woman shrugs and says, “I’m unaffiliated.” An earthy young woman describes herself as a “Jewess,” while a 20-something hipster declares that he is a “bad Jew”—staring ironically into the camera. Finally, New York performance artist Vanessa Hidary performs her hip-hop influenced poem Hebrew Mamita, inspired by the revulsion she felt when a guy in a bar tried to compliment her by saying that she didn’t “look Jewish.”

“This is a style I’ve developed over my whole filmmaking career,” says Shlain, who has made eight short films since 1990. “I studied avant-garde film, and my style is very experimental.”

Her style works all the more because, as filmmakers from Michael Moore to Morgan Spurlock have done, Shlain balances her teasing humor with a serious undercurrent. As the narrator discusses the Diaspora, the screen shows a dandelion with the wind slowly blowing its seeds away. The next shot is a timeline of expulsions, pogroms and other attacks against Jews, from the Assyrian Exile to the Nazi Holocaust, and the viewer is overwhelmed by the sheer number. At that point, the same red dot, used to represent the tiny proportion of Jews in the world population gets cut in half.

“When we show that persecution list and the dot, you get a big gasp in the audience where they get it,” Shlain says. “A lot of people, especially people of other faiths, have come up to me afterward to talk about that.”

The Tribe premiered last January at the prestigious Sundance Film Festival and since then has won awards at festivals in San Francisco, Nashville and Ann Arbor, Mich. It is available for purchase at Shlain’s Web site (www.TribetheFilm.com), where it comes with a short book exploring the ideas in the film, as well as a deck of “discussion cards” laden with thoughtprovoking images and words. And, of course, the site includes opportunities for people to post their reactions.

One such reaction reads, “I was brought up in a kosher Conservative Jewish home, had a bat mitzvah and then ran away from my Judaism for many years. Your work really connected me to a very new perspective. I still have not found my tribe but I would like to renew the search … thanks for the push.”

Jeff Fleischer is a Chicago-based freelance writer. His work has appeared in The New Republic, Mother Jones and Mental Floss.

Tags: barbie, film, jeff fleischer, jewish, the tribe, world jewish digest