by Jeff Fleischer

(World Jewish Digest, August 2007)

In the four-plus years since Sudan’s western Darfur region became the site of this century’s first genocide, somewhere between 200,000 and 400,000 people have been killed by governmentbacked Janjaweed militias. The crisis has created more than 2.5 million refugees, many of them housed in camps near the border with Chad, and an estimated 3.5 million people are in danger of starvation.

While the familiar cries of “Never Again” have spurred citizen activism throughout the world, the United States and other countries have largely failed to intervene. And so, the large-scale killing, raping and looting continue.

On June 12, Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir finally agreed to allow the United Nations to send a long-debated hybrid United Nations-African Union peacekeeping force into Darfur. Days earlier, the United States issued a set of sanctions against Sudan, designating 30 Sudanese companies as complicit in the genocide. However, it’s not clear whether these steps will actually help end the genocide. The government in Khartoum has previously agreed to ceasefires with Darfuri rebel groups only to violate them, and a hybrid force could still face obstacles to implementation.

In July 2004, the American Jewish World Service and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum hosted an emergency summit on Darfur, bringing together more than 40 nonprofit groups concerned with the Darfur genocide. Jewish organizations have continued to play key roles in raising awareness and money for humanitarian efforts, helping sustain the refugee population and appealing to governments in the hopes of urging intervention.

“For a while, the so-called civilized world knew about it and preferred to look away,” Prof. Elie Wiesel said at that summit. “Now people know. And so they have no excuse for their passivity bordering on indifference. Those who … try to break the walls of their apathy deserve everyone’s support and everyone’s solidarity.”

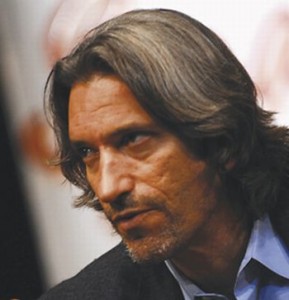

For as long as the genocide in Darfur has been going on, human-rights activist John Prendergast has been speaking out and working to stop the violence. A former State Department official during the Clinton administration, he is a senior advisor to the International Crisis Group and co-founder of the ENOUGH Project to end genocide. Along with Hotel Rwanda star Don Cheadle, he is also the co-author of the recent book “Not on Our Watch,” which details the roots of the Darfur crisis and outlines steps citizens can take to get involved.

Prendergast recently spoke with World Jewish Digest.

World Jewish Digest (WJD): You’ve personally visited Darfur at various points since the genocide began. How has the situation on the ground changed during that span?

John Prendergast (JP): Of course, what we saw in ‘03 and ‘04 was the height of the massive ethnic-cleansing push by the government and its associated militias. What we have now is Phase II of this process, with people penned up in camps, at risk of disease and starvation. The aid is being restricted at times or aid agencies are unable to access civilian populations because of the insecurity in many places; government-associated militias are attacking humanitarian convoys as well as civilian populations. So we have a pretty wicked and lethal cocktail of different forms and sources of violence that are contributing to a slow and steady deterioration of the situation. So you had one big bang earlier, and now it’s the slow erosion of people’s ability to survive.

WJD: Because the Sudan government has interfered with aid from the beginning, how have humanitarian groups been able to get aid to the refugees?

JP: It’s been mostly through some strong and aggressive public diplomacy that’s been conducted, particularly by the United Nations and by European governments through the British. That combination made it harder for the government to do what it used to do in southern Sudan, which was just flat-out cut off aid agencies from doing their business. They’re much more clever now, but there are holes in the government’s ability to undermine humanitarian operations because they’re trying to be perceived as being constructive. They still have the capacity to do serious damage and restrict aid into local areas, but it’s less than it used to be.

WJD: Since that initial bang in 2003-04, how else have the Khartoum government and the Janjaweed changed their tactics and approach to the violence?

JP: There’s still the use of food as a weapon, the government’s continued use of bombing and attacks on villages, the support for militia attacks on aid agency personnel and infrastructure. Those have been the principal tools. It also has to be understood that today’s outcome in Darfur—which is largely a state of chaotic, ungoverned spaces interspersed with highly organized government islands—is part of the strategy. The government strategy from the beginning was to sow chaos throughout Darfur as part of a divide-and-conquer approach.

Unfortunately, it’s worked fantastically well. They’ve armed communal militias to attack neighboring communities, thus driving wedges between these groups. Inspiring conflict between Arab and non-Arab groups, between Arab groups themselves, between non-Arab groups. It’s been a very successful campaign of divide and destroy. So that’s the backdrop. Now we take the present-day picture of Darfur and see that it’s chaotic, but that didn’t just happen; it’s what the government intended to happen.

WJD: They’ve also divided the rebel groups in Darfur by using negotiation as a ploy, such as negotiating treaties with only particular rebel groups.

JP: That’s understandable; give them credit for dividing the opposition further. It’s to the discredit of the international putative peacemakers, the ones who have dipped in and out of this Darfur crisis, to try to negotiate things on occasion. Including, most egregiously, the United States and former Deputy Secretary [of State] Robert Zoellick, who came in for a few days last year in May and brokered the Darfur Peace Agreement that’s been so destructive in Darfur. [Editor’s Note: The DPA was negotiated with only one rebel group, the Sudan Liberation Army, and caused splits within that group.]

WJD: On that front, it’s been three years now since Colin Powell first used the word ‘genocide’ to describe the crisis in Darfur, and both George Bush and John Kerry followed suit during the 2004 election. But the U.S. has not acted on its commitments under the U.N. convention on genocide, so what impact has calling it ‘genocide’ had on the conflict?

JP: It’s a butterfly flapping its wings. It’s had no impact except in academic circles, where they debate whether it is a ‘genocide’ or not. It’s also diverted attention from the real question of what are we going to do. At one point, for a year after that declaration, there was almost a litmus test. If you didn’t call it genocide—regardless of what you did—if you didn’t call it genocide, you weren’t ‘strong’ in responding to the crisis in Darfur.

In retrospect, that’s extremely silly. The administration never had any desire to do anything more than what they were doing, which was basically sending some money, and they said as much right then. Colin Powell said something like ‘we’re already doing all we can’—exactly replicating the language of the genocide convention itself. It’s diverted attention from solutions, and it’s unfortunately rendered this wonderful convention—which we all thought would have such meaning if actually employed while a genocide was ongoing— into just a bankrupt international legal tool that doesn’t mean anything without the political will to implement it. It now means as much as the paper it’s printed on.

WJD: In previous conflicts with the regime in Khartoum, such as its support for Osama bin Laden or the civil war in southern Sudan, the U.S. has been able to get results through pressure. What lessons should the U.S. have learned and why haven’t they been applied to Darfur?

JP: You’d think the lessons would be abundantly obvious to them. When we’ve moved the Khartoum regime in the past, it’s been a combination of real significant pressures and some measure of military threat. You look at some examples over the last decade. The terrorism issue, first and foremost, where we’ve turned their position around on housing Al Qaeda and supporting terrorism. Remember the aftermath of 9/11, when some U.S. officials were making threats about what they might to do to countries collaborating? This changed the government of Sudan’s calculations quite rapidly. You also had the slavery example in southern Sudan in the 90’s where, as the result of multilateral pressure, they stepped back. The peace deal in 2005 between the north and south was also a similar outcome of pressures, including some robust diplomacy. These are all good examples of how, if the international community really wanted a solution in Darfur, they could move everything forward much more quickly.

WJD: The United States and other countries have shown in other situations that they’ll act without U.N. support when they want to. But we keep hearing about the ties of China and Russia to Sudan and its oil industry preventing the international community from getting involved.

JP: That’s just an excuse for inaction. The Chinese and Russians, since the end of the Cold War, have never vetoed a Security Council resolution about Africa. When we really want the Chinese and Russians with us, we work with them and negotiate with them.

WJD: When the U.S. and other countries have talked to Khartoum, it seems like they’ve offered incentives rather than apply the kinds of pressures you mentioned earlier.

JP: The reason they’ve done that—especially the U.S. because other countries wait until they see what the U.S. will do—[is] because of the counterterrorism relationship the United States now has with Khartoum. I think that’s blunted the willingness of Washington to use the kind of punitive measures we should be using to gain the compliance of Khartoum for a real peace deal and a protection force in Darfur. In the absence of that kind of commitment on the part of the internationals, the government of Sudan is not going to change its behavior.

WJD: On May 29, the Bush administration outlined a sanctions package against the government of Sudan and some Sudanese companies. What kind of impact, if any, will these new sanctions have?

JP: No impact. It’s really just posturing and pandering to domestic constituencies in the U.S. To introduce further unilateral measures that only apply to the United States has not only been completely discounted by the Sudanese; they’ve already determined how to get around unilateral sanctions. It also alienates everyone because the U.S. turns around and says, ‘Now that we’ve done what we want to do, everyone else should follow.’ That just isn’t working these days in the international arena. The better thing that has to happen is we have to more humbly come to other countries that have influence and work through the United Nations Security Council to multilateralize all these things we’ve been imposing and introducing unilaterally. We need multilateral targeted sanctions against key figures in the regime. Until we do that, there’ll be no impact from this stuff. It’s just posturing.

WJD: What are some sanctions that might work? What would those involve?

JP: Really, just working through the Security Council to go after some of the leading actors in the regime who have been responsible and maybe a rebel leader or two if he is responsible for any of these attacks or obstruction. Hitting them with travel bans and asset freezes multilaterally, so they can’t work around a smaller ban. And then going after some of the Sudanese-owned companies that have been key in helping fund the government and its arms purchases. It’s targeted sanctions and also sharing intelligence about these figures. These kind of punitive measures would help pressure the regime in Khartoum.

WJD: Looking at the United Nations’ role, U.N. officials have recently talked about providing support or extra forces to assist the African Union peacekeepers there, and Sudan has claimed it will accept that. At this point, how much do additional troops matter?

JP: It matters. It’s one thing to send support, but another to deploy what the international community has agreed to, which is this hybrid force that the U.N. would have command and control over. That’s what would make a bit of a difference, instead of the ad-hoc arrangements that have been going on up to now, like the African Union-only force. Until we have that Security Council-blessed, mandated peacekeeping mission from the A.U. and the U.N., I don’t think anything on the ground is going to change.

What we’ve had with the African Union-only troops is a small force, a drop in the bucket. Its mandate, which is just observation, is too weak. They don’t have any of the right equipment or resources necessary to undertake the kind of movement and swift response that is necessary to gain compliance. In the absence of all that stuff, it’s been a shaky enterprise.

WJD: At this point, where the genocide has been going on since February 2003, what gives you hope that it can be stopped before it fully succeeds?

JP: There are people all over the world who take the idea of ‘Never Again’ seriously, even if their governments don’t. By doing divestment campaigns, writing to members of Congress, joining humanitarian organizations, they’re the best way to put pressure on their governments and shame them into action.

Jeff Fleischer is a Chicago-based journalist who has written for publications including Mother Jones, the Sydney Morning Herald, The New Republic, the Chicago Daily Herald, Chicago Magazine and Mental Floss.

Tags: darfur, genocide, interview, jeff fleischer, jewish, john prendergast, sudan, world jewish digest